‘Gone with the Wind’ isn’t gone …

Author Carmel

“Gone with the Wind” front cover

I originally blogged about Gone with the Wind, back in 2011 and became very excited when I read an interesting article below written by Charles McGrath for The New York Times website. www.nytimes.com

For those who don’t know, Gone with the Wind is a novel written by Margaret Mitchell, first published in 1936. From Wikipedia – en.wikipedia.org : The story is set in Clayton County and Atlanta, both in Georgia, during the American Civil War and Reconstruction era. It depicts the struggles of young Scarlett O’Hara, the spoiled daughter of a well-to-do plantation owner, who must use every means at her disposal to claw her way out of the poverty she finds herself in after Sherman’s March to the Sea.

A historical novel, the story is a Bildungsroman or coming-of-age story, with the title taken from a poem written by Ernest Dowson.

Gone with the Wind was popular with American readers from the outset and was the top American fiction bestseller in the year it was published and in 1937. As of 2014, a Harris poll found it to be the second favorite book of American readers, just behind the Bible. More than 30 million copies have been printed worldwide.

Written from the perspective of the slaveholder, Gone with the Wind is Southern plantation fiction. Its portrayal of slavery and African Americans is controversial, as well as its use of a racial epithet and ethnic slurs. However, the novel has become a reference point for subsequent writers about the South, both black and white. Scholars at American universities refer to it in their writings, interpret and study it. The novel has been absorbed into American popular culture.

Margaret Mitchell was imaginative in the use of color symbolism, especially the colors red and green, which surround Scarlett O’Hara. Mitchell identified the primary theme as survival. She left the ending speculative for the reader, however. She was often asked what became of her lovers, Rhett and Scarlett. She replied, “For all I know, Rhett may have found someone else who was less difficult.”

Two sequels authorized by Mitchell’s estate were published more than a half century later. A parody was also produced.

Mitchell received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for the book in 1937. It was adapted into a 1939 American film. The book is often read or misread through the film. Gone with the Wind is the only novel by Mitchell published during her lifetime.

A Piece of ‘Gone With the Wind’ Isn’t Gone After All

By CHARLES McGRATH www.nytimes.com

Published: March 29, 2011

Wendy Carlson for The New York Times

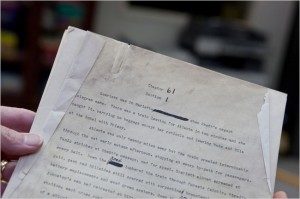

A page from the final draft of a late chapter of “Gone With the Wind.”

The chapters, which contain some of the novel’s most memorable lines — like, “My dear, I don’t give a damn” and “After all, tomorrow is another day” — were given to the Pequot in the early 1950s by George Brett Jr., the president of Macmillan, Mitchell’s publisher, and a longtime benefactor of the library. Some pages from the manuscript were actually displayed at the Pequot twice before — in a 1979 exhibition of Macmillan first editions, also donated by Mr. Brett, and in 1991 for a show honoring “Scarlett,” Alexandra Ripley’s authorized, if not very good, sequel to “Gone With the Wind.” But Dan Snydacker, executive director of the library, said nobody back then paid the manuscript much attention or recognized its importance.

The pages went back into storage and resurfaced only in response to a query from Ellen F. Brown, who was working with her co-author, John Wiley Jr., on “Margaret Mitchell’s ‘Gone With the Wind’: A Bestseller’s Odyssey From Atlanta to Hollywood,” published in February by Taylor Trade Publishing. Ms. Brown was interested in the Brett collection at the Pequot and curious to know if any of the library’s many foreign editions of “Gone With the Wind,” yet another bequest, had inscriptions from the author to her publisher. They do, but most, it turns out, are pretty tepid. For at least part of the time, the relationship between Mitchell and Brett was somewhat frosty, and why Brett had the manuscript in the first place remains a mystery.

The manuscript itself is remarkably clean, typed on a Royal portable with just a few handwritten corrections fixing a typo, adding a word or changing a “that” to a “which,” often incorrectly. That it’s in this condition suggests something about Mitchell’s perfectionist nature and something about the unusual way “Gone With the Wind” was written and published. Mitchell worked on the novel, which was originally to be called either “Tomorrow Is Another Day” or “Tote the Weary Load,” in fits and starts from 1925 to 1935. She wrote on blank newsprint and composed the book out of order, beginning with the last chapter and picking up other sections as her mood suited her. The finished chapters she put in individual manila envelopes, sometimes with grocery lists scrawled on them, and stored in a closet. Very few people saw them or even knew what she was doing.

In April 1935, however, while on a scouting trip to Atlanta, Harold Latham, the editor in chief of Macmillan, somehow pried the pile of envelopes loose from Mitchell and sent them to New York for evaluation. Ms. Brown said the draft at that point was a mess, with some chapters missing and duplicate versions of others, and yet Macmillan reacted enthusiastically and decided, with unusual haste, to bring the novel out the following spring. From August 1935 to January 1936, Mitchell, with the help of John Marsh, her second husband (and best man at her marriage to the first), and some hired typists and stenographers, essentially rewrote and retyped the entire book, cutting, refining, straightening out inconsistencies and fixing historical inaccuracies. Until fairly late in the process the heroine was called Pansy, and when Mitchell changed the name to Scarlett, thank goodness, she paid 50 cents an hour to have every page mentioning Pansy retyped.

As each chapter was finished, it was sent off to New York, and that typescript, with very few alterations, became the final text of the novel. The manuscript you would really like to see is that jumble of newsprint pages stuffed into envelopes — what Macmillan called “MS of the Old South” — but most of that was destroyed by Mitchell’s husband, following her instructions, after her death in 1949. Mitchell always insisted that books should be judged by their final versions, not their drafts, and had grown weary of people and institutions pestering her for manuscript pages to be kept as souvenirs or put on display. Marsh also burned, or so it was thought, most of the final typescript. He kept back two chapters, 44 and 47, which, along with some of the earlier material, are now stored in a vault in Atlanta, to be opened only if a question ever arises about the authorship of “Gone With the Wind.”

So what was George Brett doing with the last four chapters? At one point he didn’t even know he had them. That was in 1936, when he wrote to Mitchell asking if he could have a couple of manuscript pages to display at The New York Times Book Fair that year. Mitchell wrote back, irritated, to say that the manuscript had never been returned to her. Abashed, Macmillan found it in a vault and, insuring it for $1,000, sent it all back, or so everyone believed until just recently. Mr. Snydacker said there were only a few explanations. Either Brett held onto part of the manuscript deliberately, or some of the chapters became separated (one of the pages, dusty and with a rusty paperclip mark, looks as if it had been stored on a windowsill somewhere), or Mitchell asked him to hold onto the chapters for safekeeping.“It’s easy to give him the benefit of the doubt,” Joan Youngken, the guest curator of the Pequot exhibit, said. “If he kept it improperly, he wouldn’t be passing it along to a public library.” Ms. Brown said: “I think those chapters must have been a gift. The story has always been that Mitchell and Brett didn’t get along because she felt he didn’t make a good enough deal for the movie rights. And it’s true that he didn’t. There are some angry letters, and there was a period when they weren’t speaking. But I’ve found plenty of evidence that by the end they had a very warm relationship.”

Carefully turning over the pages of the manuscript last week, Mr. Snydacker said: “I think it’s amazing that we have this. I love the book even though it’s inexcusably racist. It wasn’t written in the 1860s but the 1930s, for God’s sake. In some ways it’s pretty sympathetic to the K.K.K. But it’s a great work in spite of that. It’s a very powerful antiwar book, among other things. As a Vietnam vet, that part has always rung true to me, and I think that’s why it was so popular in Europe.” He added: “No question, ‘Gone With the Wind’ is a part of the fabric of American life, and not just the movie, either. The book still sells something like 250,000 copies a year.”

To read more go to Books: www.nytimes.com

Leave a Reply