Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs

As I have been up to my ears in notes about Egypt writing book 3 of the ‘Daughters of the Wind’ series, I thought for this Thursday Art-Day it might be interesting to mention the captivating exhibition Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs at the Melbourne Museum. The exhibition is on display from April through to November 2011. More than 130 artefacts, including 50 from the tomb of Tutankhamun, are on display. I am wondering how I can find the time for a trip to Melbourne! The exhibition includes statues, mummies, jewellery and weapons along with the crown from the young pharaoh’s resting place in the Valley of the Kings.

Where: Melbourne Museum Carlton Gardens, Nicholson Street, Carlton, Melbourne

Tickets: Bookings available through Ticketek 132 849 and www.KingTutMelbourne.com.au.

Tutankhamun

Adapted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia www.wikipedia.com

Tutankhamun (alternately spelled with Tutenkh-, -amen, -amon), approx. 1341 BC – 1323 BC) was an Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (ruled c.1333 BC – 1323 BC in the conventional chronology), during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom. His original name, Tutankhaten, means “Living Image of Aten”, while Tutankhamun means “Living Image of Amun”. In hieroglyphs, the name Tutankhamun was typically written Amen-tut-ankh, because of a scribal custom that placed a divine name at the beginning of a phrase to show appropriate reverence. He is possibly also the Nibhurrereya of the Amarna letters, and likely the 18th dynasty king ‘Rathotis’ who, according to Manetho, an ancient historian, had reigned for nine years — a figure which conforms with Flavius Josephuss version of Manetho’s Epitome.

The 1922 discovery by Howard Carter and George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon of Tutankhamun’s nearly intact tomb received worldwide press coverage. It sparked a renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, for which Tutankhamun’s burial mask remains the popular symbol. Exhibits of artifacts from his tomb have toured the world. In February 2010, the results of DNA tests confirmed that he was the son of Akhenaten (mummy KV55) and his sister/wife (mummy KV35YL), whose name is unknown but whose remains are positively identified as “The Younger Lady” mummy found in KV35.

Tutankhamun was the son of Akhenaten (formerly Amenhotep IV) and one of Akhenaten’s sisters. As a prince he was known as Tutankhaten. He ascended to the throne in 1333 BC, at the age of nine or ten, taking the reign name of Tutankhamun. His wet-nurse was a woman called Maia, known from her tomb at Saqqara.

When he became king, he married his half-sister, Ankhesenepatan, who later changed her name to Ankhesenamun. They had two daughters, both stillborn. Given his age, the king probably had very powerful advisers, presumably including General Horemheb, the Vizier Ay, and Maya, the “Overseer of the Treasury”. Horemheb records that the king appointed him ‘lord of the land’ as hereditary prince to maintain law.

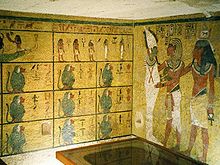

Tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings

Reign

Cartouches of his birth and throne names are displayed between rampant Sekhmet lioness warrior images (perhaps with his head) crushing enemies of several ethnicities, while Nekhbet flies protectively above.

King Tutankhamun Cartouches

Slight of build, and roughly 170 cm (5 ft 7 in) tall, Tutankhamun had large front incisors and the overbite characteristic of the Thutmosid royal line to which he belonged. He also had a pronounced dolichocephalic (elongated) skull, although it was within normal bounds and highly unlikely to have been pathological. Given the fact that many of the royal depictions of Akhenaten often featured such an elongated head, it is likely an exaggeration of a family trait, rather than a distinct abnormality. The research also showed that the Tutankhamun had “a slightly cleft palate” and possibly a mild case of scoliosis.

Anubis

There are no surviving records of Tutankhamun’s final days. What caused Tutankhamun’s death has been the subject of considerable debate. Major studies have been conducted in an effort to establish the cause of death. Although there is some speculation that Tutankhamun was assassinated, the general consensus is that his death was accidental. A CT scan taken in 2005 shows that he had badly broken his leg shortly before his death, and that the leg had become infected. DNA analysis conducted in 2010 showed the presence of malaria in his system. It is believed that these two conditions (malaria and leiomyomas) combined, led to his death.

According to the September 2010 issue of National Geographic magazine, Tutankhamun was the result of a incestuous relationship and, because of that, may have suffered from several genetic defects that contributed to his early death. For years, scientists have tried to unravel ancient clues as to why the boy king of Egypt, who reigned for 10 years, died at the age of 18. Several theories have been put forth; one was that he was killed by a blow to the head. Another put the blame on a broken leg. As recently as June 2010, German scientists said they believe there is evidence he died of sickle cell disease.

As stated above, the team discovered DNA from several strains of a parasite proving he was infected with the most severe strain of malaria several times in his short life. Malaria can trigger circulatory shock or cause a fatal immune response in the body, either of which can lead to death. If Tutankhamun did suffer from a bone disease which was crippling, it may not have been fatal. “Perhaps he struggled against others [congenital flaws] until a severe bout of malaria or a leg broken in an accident added one strain too many to a body that could no longer carry the load,” wrote Zahi Hawass, archeologist and head of Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquity involved in the research.

Tutankhamun’s chest now in the Cairo Museum.

Tutankhamun was buried in a tomb that was small relative to his status. His death may have occurred unexpectedly, before the completion of a grander royal tomb, so that his mummy was buried in a tomb intended for someone else. This would preserve the observance of the customary seventy days between death and burial.

King Tutankhamun’s mummy still rests in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings. On November 4, 2007, 85 years to the day after Carter’s discovery, the 19-year-old pharaoh went on display in his underground tomb at Luxor, when the linen-wrapped mummy was removed from its golden sarcophagus to a climate-controlled glass box. The case was designed to prevent the heightened rate of decomposition caused by the humidity and warmth from tourists visiting the tomb.

Tutankhamun seems to have faded from public consciousness in Ancient Egypt within a short time after his death, and remained virtually unknown until the 1920s. His tomb was robbed at least twice in antiquity, but based on the items taken (including perishable oils and perfumes) and the evidence of restoration of the tomb after the intrusions, it seems clear that these robberies took place within several months at most of the initial burial. Eventually the location of the tomb was lost because it had come to be buried by stone chips from subsequent tombs, either dumped there or washed there by floods. In the years that followed, some huts for workers were built over the tomb entrance, clearly not knowing what lay beneath. When at the end of the twentieth dynasty the Valley of the Kings burials were systematically dismantled, the burial of Tutankhamun was overlooked, presumably because knowledge of it had been lost and his name may have been forgotten.

2 Responses

tracey

I’d love to see this.

Shaun Kolk

I certainly enjoy this and am trying myself to get some Extra information and detail on this.