Thursday Art-Day – Sir Edwin Henry Landseer RA (7 March 1802 – 1 October 1873)

Words: Carmel Rowley & www.wikipedia.org

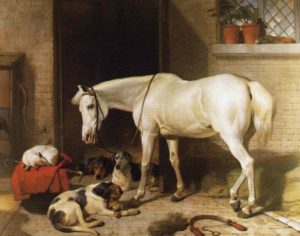

Arab Stallion

I blogged about Sir Edwin Henry Landseer and his incredible paintings way back in 2011. During this week I posted Landseer’s The Arab Tent with a previous blog so I thought it was the perfect time to revisit Landseer’s fascinating life again. Most Arabian horse breeders know of or possibly have a framed print of The Arab Tent on their wall. But do you know about this extraordinary artist? So once again for Thursday Art-Day we take a look at the art and the life of Sir Edwin Henry Landseer.

The Arab Tent

Landseer was something of a prodigy whose artistic talents were recognised early on; he studied under several artists, including his father John Landseer, an engraver, and Benjamin Robert Haydon, the well-known and controversial history painter who encouraged the young Landseer to perform dissections in order to fully understand animal musculature and skeletal structure.

Landseer’s life was entwined with the Royal Academy. At the age of just 13, in 1815, he exhibited works there. He was elected an Associate at the age of 24, and an Academician five years later in 1831. He was knighted in 1850, and although elected President in 1866 he declined the invitation. A notable figure in 19th century British art, his works can be found in Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, Kenwood House and the Wallace Collection in London. He also collaborated with fellow painter Frederick Richard Lee. Landseer’s popularity in Victorian Britain was considerable. He was widely regarded as one of the foremost animal painters of his time, and reproductions of his works were commonly found in middle-class homes. Yet his appeal crossed class boundaries, for Landseer was quite popular with the British aristocracy as well, including Queen Victoria, who commissioned numerous portraits of her family (and pets) from the artist.

An Old Cover Hack

Landseer was particularly associated with Scotland and the Scottish Highlands, which provided the subjects (both human and animal) for many of his important paintings, including his early successes The Hunting of Chevy Chase (1825–1826) and An Illicit Whiskey Still in the Highlands (1826–1829), and his more mature achievements such as the majestic stag study Monarch of the Glen (1851) and Rent Day in the Wilderness (1855–1868). Laying Down The Law (1840) satirises the legal profession through anthropomorphism.

Head of Deerhound

(c) Leeds Museums and Galleries (book); Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

So popular and influential were Landseer’s paintings of dogs in the service of humanity that the name Landseer came to be the official name for the variety of Newfoundland dog that, rather than being black or mostly black, features a mix of both black and white; it was this variety Landseer popularised in his paintings celebrating Newfoundlands as water rescue dogs, most notably Off to the Rescue (1827), A Distinguished Member of the Humane Society (1838), and Saved (1856), which combines Victorian constructions of childhood with the appealing idea of noble animals devoted to humankind—a devotion indicated, in Saved, by the fact the dog has rescued the child without any apparent human direction or intervention.

Monarch of the Glen (1851)

In his late 30’s Landseer suffered what is now believed to be a substantial nervous breakdown, and for the rest of his life was troubled by recurring bouts of melancholy, hypochondria, and depression, often aggravated by alcohol and drug use. In the last few years of his life Landseer’s mental stability was problematic, and at the request of his family he was declared insane in July 1872. Landseer’s death on 1 October 1873 was widely marked in England: shops and houses lowered their blinds, flags flew at half-staff, his bronze lions at the base of Nelson’s column were hung with wreaths, and large crowds lined the streets to watch his funeral cortege pass. Landseer was buried in St Paul’s Cathedral, London.

White Collie in a landscape.

Landseer was rumoured to be able to paint with both hands at the same time, for example, paint a horse’s head with the right and its tail with the left, simultaneously. He was also known to be able to paint extremely quickly—when the mood struck him. He could also procrastinate, sometimes for years, over certain commissions.

His painting The Shrew Tamed, entered at the 1861 Royal Academy Exhibition, caused controversy because of its subject matter. It showed a powerful horse lying in the straw in a stable while a lovely young woman lies with her head pillowed on its shoulder, lightly touching its head with her hand.

Shrew Tamed

The catalogue explained it as a portrait of a noted equestrienne, Ann Gilbert, applying the taming techniques of the famous ‘horse whisperer’ John Solomon Rarey. Critics however were troubled by the depiction of a languorous woman dominating a powerful animal, and some concluded Landseer was referencing the famous courtesan Catherine Walters, then at the height of her fame. Walters was herself an excellent horsewoman and along with other ‘pretty horsebreakers’ frequently appeared riding in Hyde Park.

The English architect Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens was named after him—Lutyens’ father was a friend of Landseer. The only contemporary animalier to approach his fame was fellow Royal Academician Richard Ansdell. After his death, Landseer left behind three unfinished paintings: Finding the Otter, Nell Gwynne and The Dead Buck, all on easels in his studio. It was his dying wish that his friend John Everett Millais should complete the paintings and so Millais did.

For more www.wikipedia.org

Leave a Reply